Notable people & Events

Elfego Baca

SOCORRO’S ELFEGO BACA: SIX-GUNS WERE HIS CALLING CARD

By Michael Hayes

The year was 1866. The Civil War had drained the nation’s economy; times were tough in the territories, as well as the 36 admitted states. Undoubtedly, it was the defeated dollar and hard times in general that drove Francisco and Juanita Baca to relocate their family via ox train from Socorro to Topeka, Kan. But their youngest child, Elfego, would never admit that. He was only a year at the time of the move, but later would say that his father was a “heavy loader” in Socorro, and that Francisco Baca had simply wanted to give his children the benefits of education that Socorro did not offer.

Elfego and his siblings did attend public school in Topeka, but in 1872 their family was struck with a tragedy. Within a three week span, Elfego’s mother, his only sister, and an older brother were claimed victim to a deadly plague. Sometime thereafter, Elfego’s father departed west, taking only his eldest son, Abdenago, with him. Elfego spent some time in a Topeka orphanage before returning to Socorro at about age 16.

In Socorro, Elfego was reunited with Abdenago and others of the Baca clan, but his father was not among them. While serving as the town marshal of Belen in neighboring Valencia County, Francisco had shot into the midst of a threatening mob, killing two men. Subsequently, he was tried for murder and found guilty in the fifth degree. He was being held in the Valencia County Jail, in Los Lunas, awaiting transfer to Kansas State Prison, when he and three other prisoners were liberated by Elfego and a 15 year old accomplice.

Newspapers reported details of the jailbreak, but only a few privileged souls knew of Elfego’s involvement in the affair. After escorting his father to El Paso, Texas, where Francisco could slip across the international border should the need arise, Elfego returned to New Mexico. He worked on isolated cattle ranches, and for a time, in the Albuquerque area, where he transported meat by wagon to Santa Fe Railroad workers. Less than two years later, he was back in Socorro and back in the limelight.

One day in January 1883, several Texas cowboys exited a Socorro saloon and rode through the Hispanic neighborhoods of the county seat in a cloud of dust and bullets. The county sheriff was in hot pursuit of the Texans when he happened upon Elfego. Elfego, who was one month shy of his eighteenth birthday, was mounted and armed, and joined in the chase at the sheriff’s request. Several miles north of Socorro, Elfego shot one of the distant fleeing horsemen in the back. Newspaper reported the death of the cowboy at the hands of an unnamed postman, and many Texans in the county chaffed at what they called a “wanton killing.” Elfego could have cared less. Later, when asked if he knew the name of the cowboy he’d killed, he replied flippantly, “He wasn’t able to tell me by the time I caught up with him.”

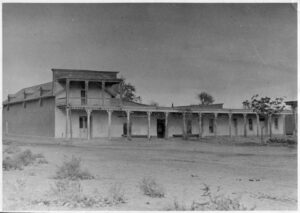

Elfego had proven himself to be wild and reckless, but he did make an attempt to settle down. In 1884 he was employed as a clerk in a mercantile owned by the mayor of Socorro, Juan Jose Baca. Mayer Baca’s mercantile, which was also his private residence, was located in the heart of Socorro, at the northeast corner of old Socorro Plaza. To anyone entering the thriving Plaza at the time, the house/mercantile would have been impossible to overlook. The sprawling, two-story adobe structure dwarfed and humbled the squat, and-story adobe buildings that surrounded it. Adding to its stateliness were elaborately trimmed territorial balcony and French doors shipped overland from St. Louis; and to its loftiness, a false front topped by a large sign that read: JUAN J. BACA.

Juan Jose paid his 19-year-old, bilingual clerk $20 a month plus room and board for his services, and if not for Elfego’s employment at the mercantile, it is likely he would have passed into history unnoticed. It was in the fall of 1884, and while at his workplace that Elfego spoke with Mayor Baca’s brother-in-law, Pedro Sarracino. Sarracino hailed from San Francisco Plaza (commonly called Frisco, and today known as Reserve), a Hispanic community of farmers and shepherds in the remote, western ranches of Socorro County. Sarracino was the proprietor of a Frisco cantina and was also a deputy sheriff of the county. He confided in Elfego that all was not well in Frisco. Several Texas cattle barons and wealthy English investors had established ranches in the area. The majority of cowboys working these ranches were Texans, some of whom delighted in terrorizing Frisco’s citizenry. Their reign of terror had recently come to a head when several cowboys tortured and maimed two Friscans in Sarracino’s cantina.

If Sarracino thought he might find a sympathetic ear in Elfego Baca, he was mistaken. Not only did Elfego disdain those who took pleasure in bullying his fellow Hispanics, he had little patience with those of his people who put up with it. And somewhere within Juan Jose Baca’s mercantile he lit into Sarracino, telling him he “should be ashamed” to call himself a lawman. Sarracino responded to the chiding by laying down his badge and challenging the teen to do better. Elfego recalled the moment in an autobiography pamphlet written in1924: “I hold him (Sarracino) that if he would take me back to Frisco with him, that I would make myself a self-made deputy.”

Elfego took leave of his mercantile job, and aboard Sarracino’s mule-drawn wagon, departed for Frisco, 130 miles to the west. In Frisco, his quest for justice culminated when he was trapped in a picket-and-mud cabin by fifty heavily armed cattlemen. From the safety of an adobe churchyard wall, the cattlemen hammered away at Elfego’s hideout with furious assaults. Their bullets easily penetrated the cabins flimsy walls; yet, for only two days, Elfego’s return gunfire held the enemy at bay.

Thanks in part to Elfego’s able marksmanship, the cabin’s sunken floor and the timely arrival of a bona fide deputy sheriff of the county, Elfego survived the battle and soon was elevated to folk hero status in the eyes of his fellow Hispanics. His popularity manifested itself when juries of his peers acquitted him of two murder charges stemming from the Frisco gun battle and when he was elected or appointed deputy sheriff, clerk, school superintendent, sheriff, district attorney of the Socorro County and mayor of the county seat in later years. In 1958, 13 years after his death, Walt Disney Productions paid tribute to Elfego’s heroics at Frisco when it produced a prime time television miniseries called The Nine Lives of Elfego Baca.

Perhaps as incredible as Elfego’s survival against the odds at Frisco is the longevity of his former workplace: the house/mercantile that dominated old Socorro Plaza throughout the latter half of the 19th century. On the brink of collapse 10 years ago, the building was purchased from granddaughters of Juan Jose Baca by a local businessman and is in the process of being restored. Changes have been made in its inner structure to make it sound and marketable, but pains are being taken to maintain its historical integrity. A Territorial-style balcony still fronts the house, and the French doors shipped over land from St. Louis by ox train still hang in the entrances. To anyone familiar with the J.J. Baca House only through early photographs, the building would be instantly and gratifyingly recognizable. To lovers of Western lore, the house that catapulted Elfego Baca into fame and legend is a landmark that shouldn’t be passed by.

The next time you’re traveling Interstate 25 south of Albuquerque; take a side trip into Socorro. Off the main drag of California Street, turn west onto San Miguel Street, park your car near the historic San Miguel Church, then mosey down Bernard Street. When you come upon the J.J. Baca House, stand under its balcony and let your mind drift back to yesteryear.

- J.J. Baca House: Photo Courtesy of the Socorro Historical Society.

- J.J. Baca House as it is today.